Over the past fifteen years, I have written extensively on distorted thinking. What we think often doesn’t match reality. Whether we confabulate reasons or rely on biased cognitive heuristics, we custom fit reality to fit our preconceived ideas, and then, are dumfounded (and angered) when somebody disagrees with our customized portrait of the world. We call this relativistic thinking. Psychology has identified many of our biased distortions, testing and validating their existence. At the top of the list is the fundamental attribution error.

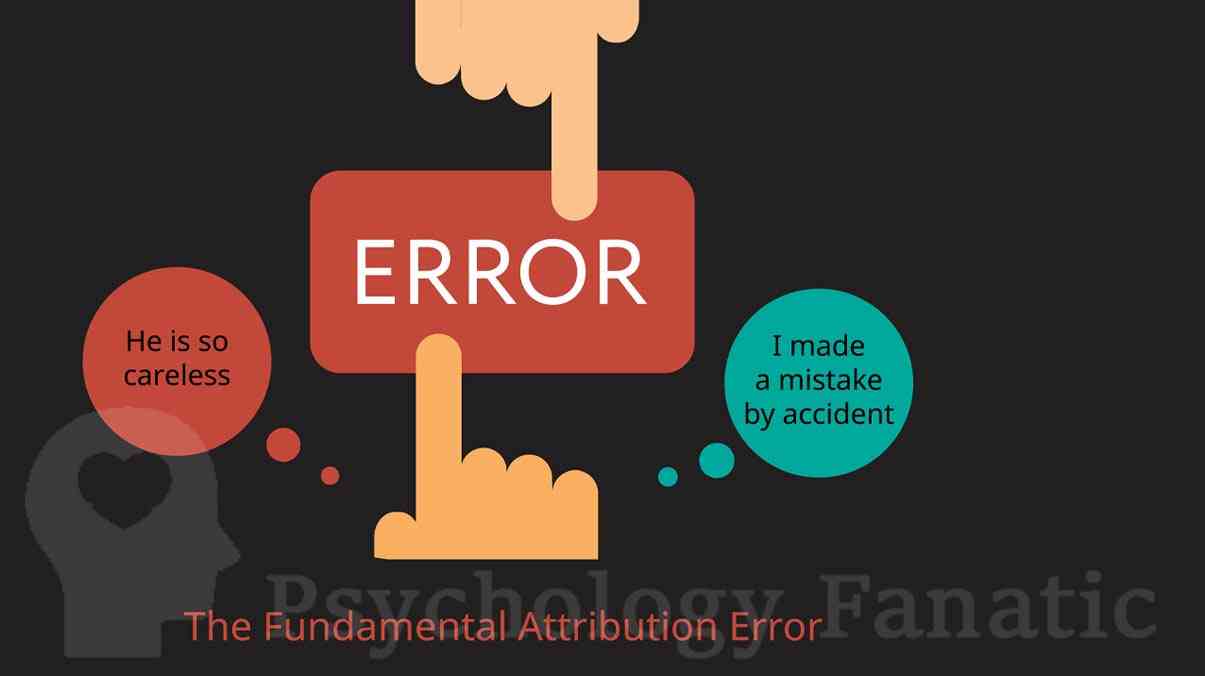

Fundamental attribution error refers to our tendency to attribute the bad actions of others to their character or personality (dispositional factors), while attributing our misdeeds to external situational factors (environmental factors) outside of our control.

We are overly lenient when explaining personal mistakes while holding others completely accountable for ethical or moral deviations. Basically, we behave bad because we are the victim of circumstances; they behave bad because they are ‘bad’.

Key Definition:

Fundamental attribution error, also known as correspondence bias, refers to the tendency of individuals to overemphasize the role of personal characteristics or traits in explaining someone else’s behavior while underemphasizing the influence of situational factors. In other words, people often have a tendency to attribute the behavior of others to their internal qualities, such as personality or disposition, rather than considering external factors that may be contributing to the behavior. This cognitive bias can lead to misunderstandings and inaccurate judgments about others.

Motivation To Assign a Cause

A driving force behind attribution errors is we constantly seek answers. We learn from experience by extracting an underlying cause. Once we identify the underlying causes, we relieve confusion by integrating the experience into current beliefs. Attributing causes gives a sense of control over the future. When we know that discussing finances before dinner leads to an argument, we can easily refrain from the discussions until bellies are full.

The problem with our attributions is we overly simplify. Complex adaptive systems, such as humans, rarely have a single identifiable cause. Our attributing of human behavior to a single identifiable cause ignores the mass of contributing causal factors (2001).

Robert Axelrod and Michael D. Cohen wrote “the problem is that the actions are frequently much easier to observe than the conditions” (2001, p. 141). We work backward, starting with the observable behavior. We see a behavior, determine whether we like it our not, and then integrate it into our current beliefs system in way not to rock the boat.

If another person’s action upsets us, we likely will attribute the upsetting stressor to a controllable feature of their personality. They could have behaved better. When we upset someone, we often defer to the circumstances. I had no choice. With others, we fail to recognize the critical role of context, while with ourselves, context becomes a ready made excuse to avoid critical questions about fundamental beliefs about ourselves (I’m a good person).

Bad things are easier to blame on outside events and successes feel better when we attribute them to personal character.

Thomas Gilovich explains, ”people are also prone to self-serving assessments when it comes to apportioning responsibility for their successes and failures” (1991). We applaud ourselves when we succeed and blame outside forces when we fail.

Dispositional Factors

Dispositional factors motivating behavior is an individual’s underlying personality, beliefs, or basically their inherent ‘goodness’ or ‘badness’. Certainly, dispositional factors play a significant role. Our dispositions are the base line. We react to outside stressors from the foundation of our disposition.

Personal development often begins when we identify a dispositional tendency that leads to behaviors we wish to change.

Situational Factors

Situational factors are the environments and circumstances influencing the behavior. These can be immediate situational factors (being stressed at the time of the behavior) or environmental factors that contribute to behavioral patterns.

Should We Minimize The Fundamental Attribution Error?

Evaluating and interpreting life is a survival skill. Accuracy is not necessarily always best. Whoa! Please, read that again. According to positive psychology, assessing negative life events as permanent, pervasive, and personal is associated with helplessness and depression.

Martin E. P. Seligman wrote, “the defining characteristic of pessimists is that they tend to believe bad events will last a long time, will undermine everything they do, and are their own fault” (2006).

According to this theory, “interpretations of current and past events in terms of any of the three components of a negative attributional style (stable, global, and internal) influence expectations for future events and, subsequently, lead to feelings of helplessness and suppress behaviors to improve their situation” (Murphy, 2022).

Impact of Attributions on Mental Health

In an often cited research paper Abramson, Metalsky, and Alloy (1989) explained that people who view negative life events through a negative cognition style (negative attribution style) and dysfunctional attitudes are at greater risk for depression.

The psychological concept of depressive realism suggests that people with mild to moderate depression are more likely to have a more realistic view of probabilities than those not suffering from depression.

In an intriguing critique of the fundamental attribution error, authors wrote, “given the difficulty in determining accuracy, it follows that situational biases in people’s attributional analyses may be just as inaccurate (involve just as much error) as dispositional biases” (Harvey, Town, and Yarkin, 1981).

Perhaps, when we judge a cognitive style, we shouldn’t just slap a label of good or bad without examining its functional consequences. If unfiltered reality shuts us down, leaving us fearfully begging for escape, by all means, cognitively reappraise, subjectively manipulate, and break-up reality into digestible chunks.

On the other hand, if our cognitive distortions soothe nasty habits, leading to failed relationships, lost jobs, or life destroying behaviors, we must quit justifying, take a painful shot of reality and begin the process of change.

The Fundamental Attribution Error is a Tendency

Not everyone utilizes this attribution style. As mentioned earlier, some people have a negative explanatory style. They attribute their failings to unchangeable dispositional factors. “I am so stupid,” they condemn. ” I ruin everything.”

These attributional styles can be just as erroneous. Misrepresenting and grossly missing the enormous collage of dispositional and situational causes.

The Fundamental Attribution Error and Judgement of Others

In close relationships with those we hold dear, we often apply the same leniency of judgment. We judge intimate partners with softness, highlighting situational causes while blindly excusing dispositional traits. Like expressed in Fritz Pearls Gestalt Prayer, we need room for our autonomy while allowing for others to express their own individual selves.

Relationship expert refers to a relationships quality of positive sentiment override as an important determinate of relationship success. In positive sentiment override, the “positive sentiments we have about the relationship and our partner override negative things our partner might do” (2011). When we believe our partner to be noble and loving, most of their behavior will be examined against that backdrop. When behaviors conflict with these beliefs, we are more likely to look for outside causes to blame. “He must be stressed about work.”

By comparison, in positive sentiment override, many relationships reach a critical juncture where the grace of positive attributions is withheld, and negative dispositional attributions reign. For example, a partner may negatively and globally attribute character traits to a partner such as, “he is angry because he is a selfish person.”

Couples on the verge of destruction routinely employ interaction styles resembling the fundamental attribution error, where they evaluate their partner as a sinister criminal and ourselves as a hapless victim. We justify our angry remarks by highlighting situational forces while simultaneously attributing our partner’s cutting words to their innate terribleness.

A Few Closing Words on Fundamental Attribution Error

Attributing causes is a messy inexact process. Complexity rules out the possibility of accurately identifying all the contributing factors. So we infuse observations with our own interpretations. As Robyn Dawes puts it “…we too readily postulate hierarchies of behavior and feelings (or spiritual “levels”) in the absence of much evidence” (1994, p. 208).

Like many psychological phenomenon, we are left to ponder the benefits and curses. In a cruel game of circular thinking, we must determine if our use of the fundamental attribution error contributes to our wellness or illness.

References:

Abramson, L., Metalsky, G., & Alloy, L. (1989). Hopelessness Depression: A Theory-Based Subtype of Depression. Psychological Review, 96(2), 358-372.

Axelrod, Robert; Cohen, Michael D. (2001). Harnessing Complexity. Basic Books; Reprint edition.

Dawes, Robyn, (1994). House of Cards – Psychology and Psychotherapy Built on Myth. Free Press; 1st edition.

Gilovich, Thomas (1991). How We Know What Isn’t So: The Fallibility of Human Reason in Everyday Life. Free Press.

Gottman, J. (2011). The Science of Trust: Emotional Attunement for Couples. W. W. Norton & Company; Illustrated edition.

Harvey, John H., Town, Jerri P. and Yarkin, Kerry L. (1981) . How fundamental is the fundamental attribution error ? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 40.2 (1981): 346-349.

Murphy, T. Franklin (2022) Negative Attribution Style. Psychology Fanatic. Published 4-28-2022. Accessed 4-29-2022.

Seligman, Martin, E. P. (2006). Learned Optimism: How to Change Your Mind and Your Life. Vintage; Reprint edition.

Resources and Articles

Please visit Psychology Fanatic’s vast selection of articles, definitions and database of referenced books.

Topic Specific Databases:

PSYCHOLOGY – EMOTIONS – RELATIONSHIPS – WELLNESS – PSYCHOLOGY TOPICS