Understanding Longitudinal Studies: A Comprehensive Overview

Longitudinal studies play a crucial role in scientific research, providing valuable insights into the dynamics of various phenomena over time. By following individuals or groups over an extended period, researchers can examine changes, trends, and correlations, and gain a deeper understanding of how variables evolve.

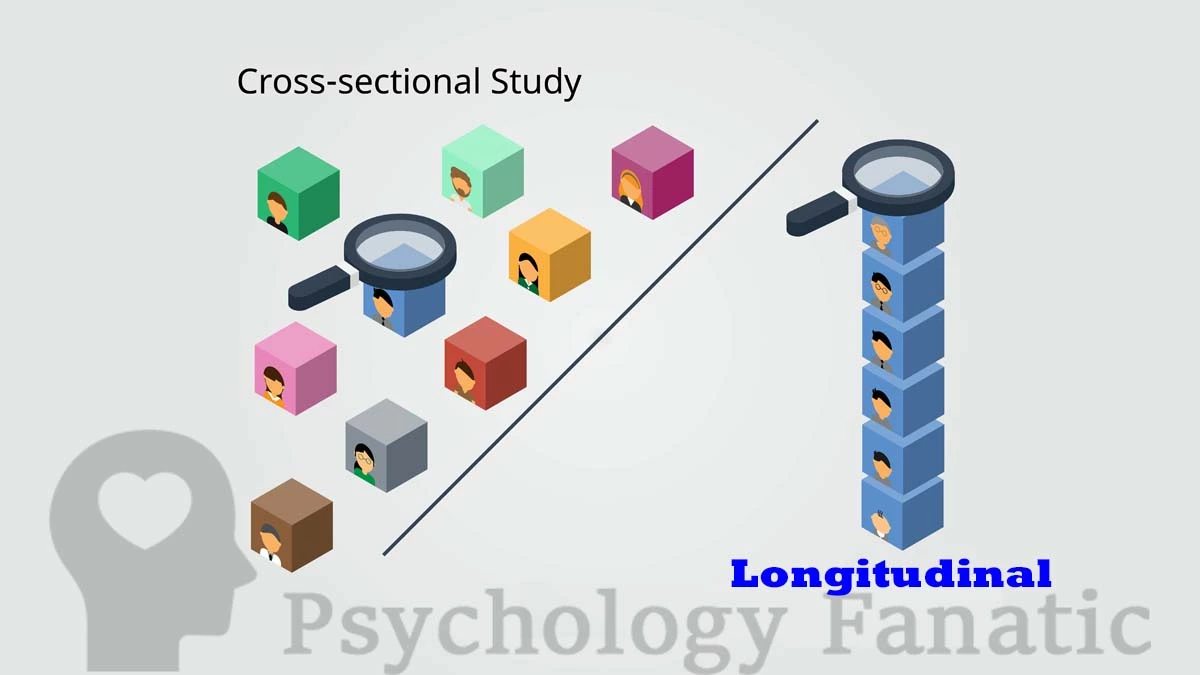

Studies on human behavior health and behavior generally are either “cross-sectional” or “longitudinal.” Cross-sectional studies “take a slice out of the world at a given moment and look inside” (Waldinger & Schulz, 2023). Most new research is from cross sectional studies. Honestly, if you are working on your doctoral dissertation, you don’t have thirty years to follow a group of people. In a cross-sectional study, takes a snapshot in time, examining variables and connections.

Key Definition:

Longitudinal study is research that involves observing and collecting data over an extended period of time.

Longitudinal studies examine lives through time. Some studies, such as the Harvard Study of Adult Development, follows subjects throughout their entire lives. These studies are not retrospective, asking questions at the end of a life span; they are prospective gathering information at regular intervals, learning about the test subjects lives as they occur (Waldinger & Schulz, 2023).

What Is a Longitudinal Study?

A longitudinal study is a research design that involves observing and collecting data from the same subjects repeatedly over an extended period. Unlike cross-sectional studies that capture a snapshot of a particular point in time, longitudinal studies offer a longitudinal perspective, enabling scientists to analyze changes and patterns over time.

Longitudinal studies provide real world views of life. We don’t live in a snapshot of time but over a course of decades. Longitudinal studies provided the fodder for the insightful life course theory. Daniel J. Sigel wrote, “life course theory and research alert us to this real world, a world in which lives are lived and where people work out paths of development as best they can. It tells us how lives are socially organized in biological and historical time, and how the resulting social pattern affects the way we think, feel and act” (Siegel, 2020, Kindle location: 8,340).

History of Longitudinal Studies

William Isaac Thomas conducted a study of Polish peasants in America and Europe following participants in the study from 1918 to 1920. His study was one of the first notable longitudinal studies. Thomas strongly suggested that there was a vital need for a ‘longitudinal approach to life history’ using recorded data. He advocated following “groups of individuals into the future, getting a continuous record of experience as they occur” (Elder, 2003, p. 3).

A few notable studies early studies were the Grant and Glueck studies beginning in the 1940’s. The Grant study followed 268 Harvard educated men whom were members of Harvard undergraduate classes of 1942, 1943, and 1944. A study conducted in tandem with the Grant study was the Glueck study which followed a cohort of 456 disadvantaged, non-delinquent inner-city youths who grew up in Boston neighborhood between 1940 and 1945. The two longitudinal studies eventually merged, now known as the Harvard Study of Adult Development. The study has continued for over eighty years, following the original subjects, their children, and even their grandchildren.

However, even into the 1950’s little other longitudinal research was conducted. Glen Elder explains, “Quite simply, the social pathways of human lives, particularly in their historical time and place, were not a common subject of study at this time.” He continues, “consequently, social scientists knew little about how people lived their lives from childhood to old age, even less about how their life pathways influenced the course of development and aging, and still less about the importance of historical and geographical contexts” (Elder, 2003, p. 4).

Human Development and Life Course Theories

It wasn’t until the 1960’s that the value of longitudinal studies was recognized. Many social and developmental scientists recognized the value of these massive sources of data. The life course movement beginning in the 1960’s relied heavily on the data now flowing from longitudinal studies. With the enormous flow of data from multiple studies, researchers were able to examine life across time, viewing entire life spans instead of small snapshots from popular cross-sectional research.

Human development researchers also found great value in the longitudinal data. Elder explains, “this wealth of data prompted a new way of thinking about human lives and development—studying life trajectories across multiple stages of life, recognizing that developmental processes extend past childhood, exploring issues of behavioral continuity and change” (Elder, 2003 p. 5).

A significant finding in many of these longitudinal studies is the power of context. A life course without examination in the proper social and political context incorrectly portrays the data. John Bynner argues that “life course research is not just about tracing individuals’ histories across time. It should set these trajectories in their geographical and social context” (Bynner, 2016).

Types of Longitudinal Studies

There are several types of longitudinal studies, each with its own unique characteristics and objectives:

- Trend Studies: Trend studies focus on changes across an entire population over time. Researchers collect data at multiple time points to identify and analyze trends and patterns. These studies are useful in understanding the long-term effects of interventions or policies on a large scale.

- Cohort Studies: Cohort studies follow a specific group of individuals or cohorts over a defined period. Researchers examine these cohorts at regular intervals, collecting data on variables of interest. Cohort studies are particularly valuable for investigating the development of diseases, tracking career paths, or studying the impact of social factors on a specific group.

- Panel Studies: Panel studies involve collecting data from the same group of individuals at multiple time points. Researchers can track changes within the group, analyze individual trajectories, and explore cause-and-effect relationships. These studies are commonly used in social sciences and psychology.

- Event-based Studies: Event-based studies focus on specific events or experiences that occur to individuals over time. Researchers collect data before, during, and after the event to assess its impact or consequences. Examples include studying the effects of natural disasters, major life events, or specific interventions.

Benefits of Longitudinal Studies

Longitudinal studies offer numerous benefits that contribute to the advancement of knowledge and understanding in various fields:

- Capturing Change: By observing changes over time, longitudinal studies help identify patterns and trends that would be missed in cross-sectional studies. This allows researchers to gain a more in-depth understanding of the complexities and dynamics of the variables under investigation. Copeland Young explains, “research questions about lifelong and intergenerational causal relationships are best answered by following respondents in real time rather than retrospectively” (Young, 1991).

- Exploring Cause and Effect: Longitudinal studies enable researchers to investigate cause-and-effect relationships. By collecting data at multiple time points, they can analyze how changes in one variable influence another over time, helping to establish correlations and causal relationships.

- Uncovering Developmental Trajectories: Longitudinal studies are valuable for understanding development and growth, both in individuals and groups. They provide insights into the factors that contribute to positive or negative outcomes and help identify critical periods for intervention.

- Informing Policy and Interventions: The long-term perspective offered by longitudinal studies is vital for informing policy decisions and shaping effective interventions. These studies provide evidence on the long-term impacts of policies, interventions, and social factors, helping policymakers make informed choices.

Challenges and Considerations

While longitudinal studies offer valuable insights, they also present several challenges and considerations:

- Attrition: Longitudinal studies require participants to be involved for an extended period, which can lead to attrition or dropout rates. Researchers must employ strategies to ensure participant retention and address potential biases introduced by attrition.

- Time and Cost: Longitudinal studies are resource-intensive and require significant time and funding commitment. Researchers must carefully plan and allocate resources to ensure the study’s feasibility and success.

- External Factors: External factors such as societal changes, technological advancements, or unforeseen events can impact the validity and generalizability of longitudinal studies. Researchers need to consider and account for these factors in their analysis.

- Data Management and Analysis: Longitudinal studies generate a vast amount of data, requiring efficient data management and analysis techniques. Researchers should employ robust statistical methods and advanced analysis tools to derive meaningful insights.

Conclusion

Longitudinal studies provide a comprehensive and dynamic perspective on the variables and phenomena they investigate. By capturing changes and patterns over time, these studies enhance our understanding of development, inform policy decisions, and provide valuable insights into cause-and-effect relationships. Although challenging, the knowledge gained through longitudinal studies contributes significantly to scientific progress and societal well-being.

Remember, whether you are a researcher or simply interested in a topic, longitudinal studies play a crucial role in unraveling the mysteries of the world around us.

Last Update: April 17, 2024

Note: This article serves as a general guide to longitudinal studies and does not constitute specific research or medical advice.

References:

Bynner, John (2016). Institutionalization of Life Course Studies. M.J. Shanahan, J.T. Mortimer, M.K. Johnson (Eds.), Handbook of the life course, vol. II, Springer, New York, pp. 27-58

Elder, Glen H., Johnson, Monica Kirkpatrick, Crosnoe, Robert (2003) The Emergence and Development of Life Course Theory. Editors Jaylen T. Mortimer, Michael J. Shanahan. Handbook of the Life Course. Springer, Boston, MA, 2003. 3-19.

Joshi, Heather (2022). Placing context in longitudinal research. Longitudinal and Life Course Studies. DOI: 10.1332/175795921×16682554193545

Siegel, Daniel J. (2020). The Developing Mind: How Relationships and the Brain Interact to Shape Who We Are. The Guilford Press; 3rd edition.

Waldinger, Robert J.; Schulz. Marc (2023). The Good Life: Lessons from the World’s Longest Scientific Study of Happiness. Simon & Schuster.

Young, Copeland (1991). Inventory of Longitudinal Studies in the Social Sciences. SAGE Publications, Inc; 1st edition.

Resources and Articles

Please visit Psychology Fanatic’s vast selection of articles, definitions and database of referenced books.

Topic Specific Databases:

PSYCHOLOGY – EMOTIONS – RELATIONSHIPS – WELLNESS – PSYCHOLOGY TOPICS